Finding a good name is sometimes the hardest part of designing an NPC. You want something more exotic than “Fred the Fighter”, but “Frewxyque the Grand Thunder Duke” becomes too hard to say with a straight face after the first first time. Baby name books can help, but some of the best names come from real-world sources. Beyond ‘Fred’ is a series that lists names from various sources broken down by region and/or time period.

This time we have Roman names. Since my interest here is in providing name ideas for RPGs, I’m not breaking these names down by Roman time-period. I’m including a list of resources at the end of this article for those wishing more in-depth information about Roman names.

This time we have Roman names. Since my interest here is in providing name ideas for RPGs, I’m not breaking these names down by Roman time-period. I’m including a list of resources at the end of this article for those wishing more in-depth information about Roman names.

(Photo courtesy of Flickr, © Conscious Vision 2007)

Roman Name Structure

Roman names had several parts, frequently becoming long and complex:

- Praenomen: A personal name. This was primarily used by family members and very close friends only. Romans had very few praenomen; typically the first child would be given the father’s praenomen (adjusted to a feminine form, if the child was a girl). The second child would receive the praenomen of someone else in the family — and uncle, perhaps.

- Nomen: Indicates which gens the person belongs to. The gens is a group of loosely organized families all sharing the same nomen. A woman would use the feminine form of the nomen, formed by substituting ‘-a’ for the ‘-us’ ending.

- Cognomen: A family name used by a group of blood relatives. It was a name unique to the individual and usually referred to something specific about him — usually a physical characteristic. Like a nickname, it wasn’t given to a child as part of the name given by his parents; it could be inherited from a male relative or chosen by concensus in the general community. Cognomen were almost never complementary — usually they were neutral, or even insulting names.

Common Praenomenia

Here are some of the most commonly used prenomen:

- Gaius/Gaia

- Lucius/Lucia

- Marcus/Marcia

- Quintus/Quinta

- Titus/Tita

- Tiberius/Tiberia

- Descimus/Descima

- Aulus/Aula

- Servius/Servia

- Appius/Appia

Common Nomenia

Here are some of the most common nomen:

- Acilius/Acilia

- Aebutius/Aebutia

- Albius/Albia

- Antonius/Antonia

- Cassius/Cassia

- Claudius/Claudia

- Calidius/Calidia

- Didius/Didia

- Fabius/Fabia

- Flavius/Flavia

- Galerius/Galeria

- Genucius/Genucia

- Laelius/Laelia

- Marius/Maria

- Mocius/Mocia

- Naevius/Naevia

- Ovidius/Ovidia

- Porcius/Porcia

- Rutilius/Rutilia

- Sentius/Sentia

- Sergius/Sergia

- Tarquitius/Tarquitia

- Tuccius/Tuccia

- Tullius/Tullia

- Vedius/Vedia

- Vibius/Vibia

- Vitruvius/Vitruvia

Common Cognomina

Here’s a list of common cognomen and their meanings. Many female cognomia are the same as the male versions:

- Aculeo/Aculeo – prickly, unfriendly

- Albus/Alba – fair-skinned, white

- Ambustus/Ambusta – scalding, burning

- Atellus/Atella – dark (haired or skinned)

- Bassus/Bassa – plump

- Bibulus/Bibula – drunkard

- Brocchus/Broccha – Toothy

- Bucco/Bucco – fool

- Caecus/Caeca – Blind

- Calidus/Calida – hot-headed, rash

- Calvus/Calva – bald

- Caninus/Canina – dog-like

- Celsus/Celsa – tall

- Cicurinus/Cicurina – mild, gentle

- Corvinus/Corvina – crow-like

- Dives/Dives – wealthy

- Dorsuo/Dorsuo – large black

- Fimbria/Fimbria – fringes, edges of clothing

- Flavus/Flava – blond-haired

- Florus/Flora – floral, blooming

- Galeo/Galeo – helmet

- Gurges/Gurges – greedy, prodigal

- Laterensis/Laterensis – from the hill-side

- Lepidus/Lepida – charming, amusing

- Licinus/Licina – spiky or bristly haired

- Lurco/Lurco – glutonous, greedy

- Macer/Macra – thin

- Merula/Merula – blackbird

- Mus/Mus – mouse

- Natta/Natta – artisan

- Paetus/Paeta – blinking, squinty

- Plancus Planca – flat-footed

- Priscus/Prisca – ancient

- Pullus/Pulla – child

- Quadratus/Quadrata – squat, stocky build

- Regulus/Regula – prince

- Rufus/Rufa – red-haired, ruddy

- Rullus/Rulla – rustic, uncultivated, boorish

- Scaeva/Scaeva – left-handed

- Silanus/Silana – nose, water-spout

- Varro/Varro – block-headed

- Varus/Vara – bow-legged

- Vatia/Vatia – knock-kneed

- Vetus/Vetus – old

Other Articles in this Series

- Beyond ‘Fred’: Italian Names for Characters

- Beyond ‘Fred’: Russian Names for Characters

- Beyond ‘Fred’: Anglo-Saxon Names for Characters

Resources:

- Behind the Name: Roman Names

- Private Life of Romans, The

- Roman Name (has lists of even more Roman names than I could fit here)

- Rome – Roman Names

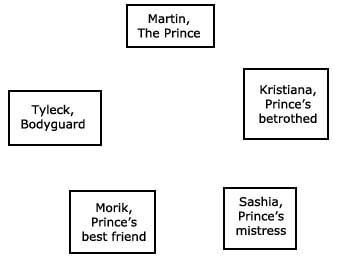

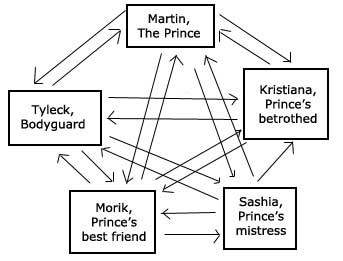

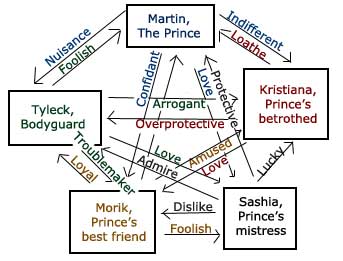

7. Along the arrows, write what each character feels about the others she knows:

7. Along the arrows, write what each character feels about the others she knows:

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=05fa4970-d028-4c9e-ab1c-740e4d4b4624)

You’ve got your NPCs classified. You’ve separated the extras and walk-ons from the bit players and major characters. But how exactly do you go about creating those unique characters? Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you create NPCs your players will remember, no matter what game system you use.

You’ve got your NPCs classified. You’ve separated the extras and walk-ons from the bit players and major characters. But how exactly do you go about creating those unique characters? Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you create NPCs your players will remember, no matter what game system you use.