What is a character web?

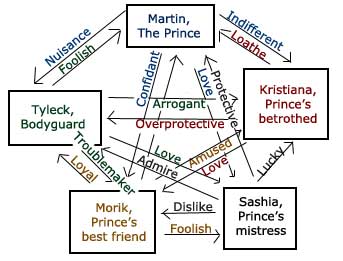

A character web is a map — a specific kind of map that charts the relationships of NPCs to one another. It’s a great tool for figuring out how one NPC may respond to another — or to anything related to that NPC. This is a tool to use with your major character NPCs; it’s not something you need to work out for every town beggar.

How do I create a character web?

- Break your NPCs into groups of who knows whom. Most likely, not all of your NPCs are going to care — or even know — about each other.

- Pick one group of NPCs to work with right now.

- Choose the leader of the group. If the group doesn’t have a leader, pick a key person.

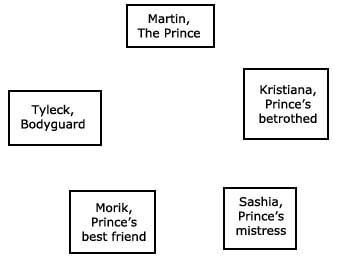

- Write their names (and small portraits, if you have them) in a circle, with your leader on top, like so:

- Decide who knows about whom in the web. It’s possible for a character not to know about one or more of the other characters in their group. For example, we can say that Martin and everyone else in this group have conspired to keep Kristiana in the dark about Sashia’s existence. But Sashia knows about Kristiana, due to a kingdom-wide announcement by Martin’s father, the king.

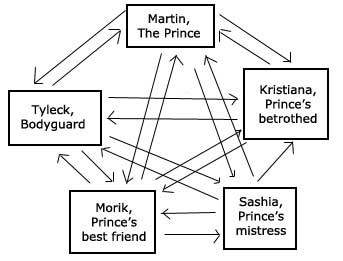

- Draw arrows from each character to every other character the web he knows about:

7. Along the arrows, write what each character feels about the others she knows:

7. Along the arrows, write what each character feels about the others she knows:

From this, we can tell the Prince’s chances at marital bliss are little to none. His soon-to-be wife loathes him, while being love with his best friend. His mistress is protective of him and consideres his betrothed to be a very lucky woman. Meanwhile, the bodyguard is in love with the mistress! Note that these are the predominant feelings of each character. Sashia isn’t going to feel protective of Martin all the time — there are times she’ll be annoyed, hurt, affectionate. But the map gives you the character’s overall attitudes towards the others around him.

Ways to use the web

In addition to helping determine how each character would relate to the others face-to-face, these webs can be used to figure out the reception the PCs might get from each one, based on how that character views the PCs in relation to others in the web.

For example: Say the Prince asked the PCs to carry a message to Kristiana. If Kristiana knows they’re coming from the Prince, she’s likely to be polite, but cold to them. After all, the last thing she wants is a message from her betrothed. However, if the PCs arrange things so that Kristiana thinks they’re coming from Morik, they’re likely to get a warm welcome and perhaps a small token of appreciation.

Another example: The PCs have been asked by the Prince’s father to substitute for Martin’s regular bodyguard for an important event. Tyleck, who feels the Prince is a foolish young man, may go along to the event on his own — just in case the Prince tries to do something stupid that the PCs won’t be expecting. He may interfere with the PC’s duties — with the best interests at heart.

A character web can provide an “at a glance” shorthand to figuring out how a given NPC may react under various situations. This can help make these characters more complex and interesting, as they don’t have the same reactions to everyone else all the time.

How about you? Do you have any tools you use to bring your NPCs to life? Please share them with us in the comments.

Related articles by Zemanta

- The Characterisation Puzzle: When personalities are hard to find (campaignmastery.com)

- Deep as a Puddle: Myers Briggs (gnomestew.com)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=05fa4970-d028-4c9e-ab1c-740e4d4b4624)

You’ve got your NPCs classified. You’ve separated the extras and walk-ons from the bit players and major characters. But how exactly do you go about creating those unique characters? Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you create NPCs your players will remember, no matter what game system you use.

You’ve got your NPCs classified. You’ve separated the extras and walk-ons from the bit players and major characters. But how exactly do you go about creating those unique characters? Here’s a step-by-step guide to help you create NPCs your players will remember, no matter what game system you use. Extras

Extras We all get them: the incessant rules lawyer who challenges your every call; the “loopholer” who will exploit everything not nailed down in the rules to gain that extra +1 advantage; the player who takes everything that happens to their character as an attack on themselves…

We all get them: the incessant rules lawyer who challenges your every call; the “loopholer” who will exploit everything not nailed down in the rules to gain that extra +1 advantage; the player who takes everything that happens to their character as an attack on themselves… So with a missing GM, you’re going to have to cancel the game for tonight, right?

So with a missing GM, you’re going to have to cancel the game for tonight, right? I have to admit, when it came out, I paid little attention to Everway. Everything I read and heard about it seemed to indicate it was a game slanted at new gamers and with 15 years of game experience under my belt at the time, why would I need a beginner’s game? Plus, with it’s box and cards it seemed … well … kitschy. But when our local game store marked their copies down to $3 apiece, I bought a set … just for the collection, of course.

I have to admit, when it came out, I paid little attention to Everway. Everything I read and heard about it seemed to indicate it was a game slanted at new gamers and with 15 years of game experience under my belt at the time, why would I need a beginner’s game? Plus, with it’s box and cards it seemed … well … kitschy. But when our local game store marked their copies down to $3 apiece, I bought a set … just for the collection, of course.