Here it is–the first post of our “Player Month”, designed to give advice to the players on how to make a game better. After all, the GM isn’t the only one playing and the players share some responsibility for making a game great.

Here it is–the first post of our “Player Month”, designed to give advice to the players on how to make a game better. After all, the GM isn’t the only one playing and the players share some responsibility for making a game great.

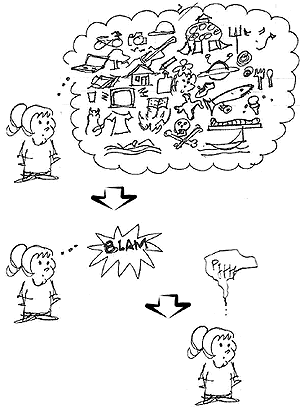

At some point or another it will happen: your GM will make a call you don’t agree with. Do you just sit there and take it? After all, it’s the GM’s game and his word is law, right?

Well, yes and no. True, the GM decides the rules and has the final say on all matters. But that’s just it: the final say is final. That doesn’t mean you can’t have your input on making that final decision before it reaches the “final” part. There’s a big difference between a ruling and a final ruling. Depending on your GM, you can sometimes make your case and see if you can reach a compromise.

The trick here is that you need to make your cases respectfully. No shouting, no temper tantrums, no storming off. Here are some tips for successful resolution with your GM.

[Image courtesy of http://www.flickr.com/photos/taylar/ / CC BY 2.0]

Figure out what you want

You need to do this before you talk to your GM. What do you want to come out of this discussion? What specific result are you looking for? It’s amazing how many players get into a “knee-jerk” reaction. They take issue with something the GM says or does, but they have no idea how they want that changed. If you have an idea of your ideal result, you can figure out a compromise much more easily.

Wait until after the session

You’re much more likely to get a positive result from a GM if you approach her after a game session, rather than during it. Bringing up an issue during the session takes up valuable play time. At best, it leaves other players with nothing to do; at worst, it opens the floor to a free-for-all argument as the other players try to put in their complaints. Not only does this make the GM feel like she’s begin ganged up on, it tends to make her dig her heels in and stick to her ruling.

Sometimes you can’t wait–for example, if your character’s about to die–and you have to deal with the issue during the session. You will, most likely, gain a better result if these cases are rare. That way, you’re more likely to get the “benefit of the doubt”, such as “Gee, he always talks to me after a session. It must be really important if he’s bringing it up now.”

Talk about specifics

When you do talk to your GM, you want to bring up a specific issue or ruling. If the GM doesn’t know exactly what’s bothering you, how can he fix it? Focusing on specifics also avoids the “Your game sucks” attitude, which is guaranteed to cause a GM to ignore anything you’ve got to say. Remember what you’re bringing up is your problem, not your GM’s.

A related point is to “marshal your argument” ahead of time. Why do you disagree with the ruling? What about it makes you unhappy or uncomfortable? Focus on how the ruling affects you and your character and cite specific examples. It’s most likely that the GM just didn’t foresee the problems you’re experiencing or didn’t see them as problems. You need to let him know why this is a problem.

Have alternative suggestions

This goes along with knowing what result you want. It’s much more likely a GM will listen and adjust things accordingly if you have some ideas on how to fix the problem. Even if she doesn’t seem to keen on changing things, having something specific to try out (“Can we try this next week and see if it works?”) is much more likely to bring a change in your favor than a “this is a problem with your game–fix it” attitude.

When you’re thinking of suggestions, take the game as a whole in to consideration. Think about how your idea(s) will affect game balance and the other players. Also consider the plot of the game as you know it so far and what you foresee happening in the future. This communicates to your GM that you’re not just looking for a result that makes you the center of the game or gives you an über-character.

Take the GM’s final word gracefully

Only your GM knows the whole game. It’s possible that the “bad” ruling needs to stand because of something that’s coming down the pipe. There’ve been many times during a game when I’ve had to say “There’s a reason, trust me.” After all, if you can’t trust your GM maybe it’s time to find a new group.

Final thoughts

As always, watch your manner and your tone as you bring anything up with your GM. Remember your Ps and Qs and common-sense advice (focus on the problem, not the person; use “I” language; remember who owns the problem, etc.).

Here it is–the first post of our “Player Month”, designed to give advice to the players on how to make a game better. After all, the GM isn’t the only one playing and the players share some responsibility for making a game great.

Here it is–the first post of our “Player Month”, designed to give advice to the players on how to make a game better. After all, the GM isn’t the only one playing and the players share some responsibility for making a game great.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=8d745098-b25d-4d91-a243-512341943814)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=39df50c0-4c5f-4ab0-aee6-21206c1efc57)

Sometimes a good background is hard to find. Usually I have no trouble coming up with a full-fledged past for my characters, complete with NPCs, subtle plot hooks, and flaws ready-made for the GM to exploit. Usually, I hand the GM a six-page character questionnaire loaded with personality quirks and background events.

Sometimes a good background is hard to find. Usually I have no trouble coming up with a full-fledged past for my characters, complete with NPCs, subtle plot hooks, and flaws ready-made for the GM to exploit. Usually, I hand the GM a six-page character questionnaire loaded with personality quirks and background events.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=538bddec-184d-4db4-b411-9c125ed451b3)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=9710b3e7-6df7-488a-8f0c-9900d4d3cbc8)

I myself have 12 hats, and each one represents a different personality. Why just be yourself?

I myself have 12 hats, and each one represents a different personality. Why just be yourself?![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=16c95a62-9a4c-4e6b-8f7d-406d93287d7a)

Sam the Bartender: Okay, you’re facing a small horde of Disgustingly Cute Furry Things and behind them are a handful of space NAZIs who seem to be driving the DCFT directly at you.

Sam the Bartender: Okay, you’re facing a small horde of Disgustingly Cute Furry Things and behind them are a handful of space NAZIs who seem to be driving the DCFT directly at you.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=a545a1db-3610-4c94-ab14-abb857a1dd4c)

Whether as a PCs or an NPCs, evil characters tend to get the short end of the stick. All too often, they’re portrayed as short-sighted, reactionary, shallow, and … well, stupid. Frequently, all evil characters look and act the same, like they are clones of one another. Which is a real shame; after all, what’s more engaging to your players than defeating a worthy opponent? Here are eight tips for making your evil characters more in-depth and engaging.

Whether as a PCs or an NPCs, evil characters tend to get the short end of the stick. All too often, they’re portrayed as short-sighted, reactionary, shallow, and … well, stupid. Frequently, all evil characters look and act the same, like they are clones of one another. Which is a real shame; after all, what’s more engaging to your players than defeating a worthy opponent? Here are eight tips for making your evil characters more in-depth and engaging.![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=08bed60d-ccd2-4f61-ab6f-a836b8dfb517)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=02679aeb-1b6a-4974-8cfc-67ac3e568893)