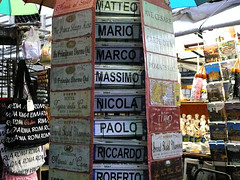

Tired of games where all the characters are named Ariel or Thorin? What a character name that sounds distinctive but not too far out? What about using a real-world name? Perhaps something historical or from another culture. In earlier editions of Beyond Fred, I covered Roman and Russian names. But what if you want something more fluid or lyrical sounding? Perhaps an Italian name will fit the bill.

Italian Name Structure

Like most Western names, Italian names are comprised of a first name followed by a last name, usually the father’s name. According to Wikipedia, occasionally in official documents the last name will be listed first.

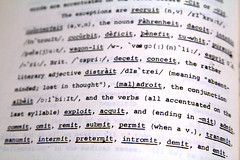

Pronouncing Italian names can be a little tricky. Pronunciation of Italian names has a search box where you can enter a name and listen to the correct pronunciation. You can also find detailed information on pronouncing Italian names at Roma Interactive.

These are by no means historically accurate. These lists are intended to be used for gaming where historical accuracy isn’t as important as how a name sounds.

Italian Names

Male Names

- Abaco

- Acario

- Addo

- Agosto

- Arrone

- Balderico

- Beltramo

- Casimiro

- Clodoveo

- Dalmazio

- Ercole

- Fedele

- Giacomo

- Lorenzo

- Lothario

- Marcello

- Massimo

- Orazio

- Pino

- Raffaele

- Raul

- Rinaldo

- Rodolfo

- Salvetore

- Serafino

- Serge

- Severino

- Tancredo

- Vencentio

- Vittore

- Zanipolo

Female Names

- Acilia

- Altea

- Aniela

- Assunta

- Benigna

- Bibiana

- Casilda

- Chiara

- Damiana

- Donata

- Esta

- Fiammetta

- Fiorella

- Ghita

- Giacinta

- Isabella

- Jolanda

- Lucia

- Marsala

- Mia

- Perla

- Rosabla

- Sidonia

- Sienna

- Tessa

- Vani

- Varanese

- Venitia

- Vittoria

- Zita

- Zola

Surnames

- Bianchi

- Cavallo

- Contadino

- de Luca

- di Genova

- Esposito

- Forni

- La Porta

- Martelli

- Montagna

- Mosca

- Rossi

- Selvaggio

- Tenagila

- Trovato

- Volpe

Other Articles in this Series

- Beyond ‘Fred’: Roman Names for Characters

- Beyond ‘Fred’: Russian Names for Characters

- Beyond ‘Fred’: Anglo-Saxon Names for Characters

Well, actually not about alphabets. While you can create a whole new alphabet for your language, it’s a lot of work to do just to create names. Especially since unless you’re writing out all of your game materials by hand, you’ve got to create either a true font or a set of

Well, actually not about alphabets. While you can create a whole new alphabet for your language, it’s a lot of work to do just to create names. Especially since unless you’re writing out all of your game materials by hand, you’ve got to create either a true font or a set of ![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=cd662975-45ae-4b8b-a18f-1447e52a2635)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=5c86ab2e-8010-4153-b0e5-62ea51e8ce82)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=422e1afc-6f4f-4be6-b869-fcf7d906d052)

(Photo courtesy of

(Photo courtesy of ![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_c.png?x-id=100d32fb-8229-4b74-b69d-3d10bbdab0d4)

This time we have Roman names. Since my interest here is in providing name ideas for RPGs, I’m not breaking these names down by Roman time-period. I’m including a list of resources at the end of this article for those wishing more in-depth information about Roman names.

This time we have Roman names. Since my interest here is in providing name ideas for RPGs, I’m not breaking these names down by Roman time-period. I’m including a list of resources at the end of this article for those wishing more in-depth information about Roman names.